The Covid-19 pandemic was a pivotal moment for online rail retailing.

As with many businesses, it was initially a major challenge.

Most of the income in the sector is volume related, whether that is commission on sales to consumers, or transaction fees charged between suppliers in the supply chain. The volume of sales collapsed, and hence so did income.

As lock-downs were eased and some travel returned, this brought new challenges. To attract customers back to rail, the industry agreed to a ‘no quibbles, no fee’ refund policy. Refunds are commercially problematic for retailers, as they hand back the commission earnt on the sale, but retain the costs of sale, and have the effort and cost of processing the refund. In normal times this is mitigated by charging customers a refund admin fee.

A third less visible challenge was that as TOCs were brought under Government control, they generally stopped their investment in their online channels and marketing. Those suppliers that worked more on a software model of selling enhancements to their clients, or agencies selling digital marketing capabilities, also saw their revenue streams dry up.

Different retailers were impacted in different ways by the pandemic. To the best of my knowledge there were two retailers that didn’t make it: Commuter Club (mentioned previously) and the initial incarnation of Virgin Trains Ticketing powered by Assertis. The pandemic was possibly also a factor in Hindsight not finding a route back to market.

Every cloud has a silver lining (sometimes more than one)

The pandemic, however, had at least two silver linings for online retail:

- It broke the habitual behaviour of season ticket holders. As people returned to the office on a ‘hybrid’ basis, they no longer needed a season ticket. People who had previously bought a season ticket once per month, were now buying day return tickets two or three days per week. It was natural for them to go online for these purchases, and become a new cohort of app users. Many of these have remained as digital customers even when they’ve reverted to buying season tickets.

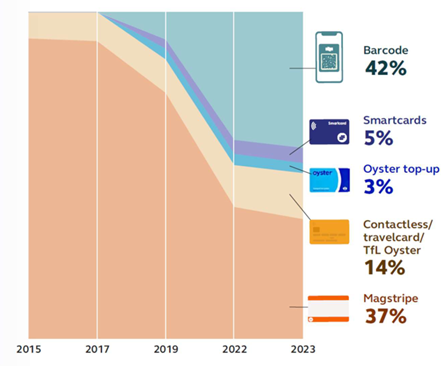

- It made QR codes acceptable. For years QR codes were ridiculed. This was largely down to their misuse in marketing, but the stigma carried over to their use in ticketing. Some industry technologists actively dismissed them as a legacy technology best left on the side of cornflakes packets. However, during the pandemic many of us found ourselves scanning QR codes to download pub menus or order a beer; many venues introduced advance bookings to manage demand, and a large part of the population suddenly found it was comfortable with the idea of using a mobile phone to book something, and to show “one of those funny square dot things” to get in.

Figure 20: Graph from RDG presentation showing the growth of mobile barcode ticketing

Every rose has a thorn

By May 2021 things were starting to turn a corner for online retail. Although overall industry volumes were still well down on 2019, online volumes had more or less recovered to pre-pandemic levels. The rail market was much more leisure travel focused, and if there was ever a time for a strong partnership between retailers and operators to throw all their weight, marketing knowhow, customer databases, and insights at getting people back on trains, it was now.

Instead, the Government announced its intention to centralise online retailing, and that the newly announced Great British Railways would be tasked with delivering its own online retail channels. This would replace all the existing TOC online retail channels:

“A single website and app will end the current confusing array of train company sites and different standards of service that passengers receive across the network. Great British Railways’ website and app will learn from the best-in-class providers today, including international partners to build a great offer for passengers.”

It concluded with a footnote:

“Independent retailers will be able to sell rail tickets, including online and in shops, and will work with Great British Railways to introduce innovations in the future.”

The choice of wording “be able to” feeling a long way from “be a valued part of”. Investors in rail retailers worried, none more visibly so than the publicly listed Trainline PLC.

Two and a half years later a further footnote would be added to the Williams-Shapps page:

“We are confirming that we are not pursuing plans to deliver a centralised Great British Railways online rail ticket retailer.”

This significant diversion had effects wider than just Trainline’s share price.

A key consequence was the virtual elimination of investment in TOC online retail channels. Investment had typically been linked to the franchise cycle, with new franchise wins typically containing a commitment to new websites, or more latterly apps, bringing additional digital features to market. Re-franchising was paused anyway as a result of the commencement of the Williams review, and now any residual investment from owning groups or third-party suppliers was largely frozen. One specific victim of this was Abellio, who were about to make their own move to their own platform, similar to Stagecoach, Arriva and Trenitalia – but the shutters came down on the final straight.

The unfortunate timing of this should not be lost. The proportion of rail journeys that were discretionary had suddenly become much greater. People had hybrid working choices, leisure journeys made up more of the market mix, business meetings could be done by Teams or Zoom. Amidst this the industry had well and truly taken its foot of the gas with online retail, which could have done so much to help stimulate growth. The two and half year diversion, undoubtedly had a material impact on recovery.

Two notable exceptions to the hiatus were LNER and Transport for Wales. LNER’s position in government ownership, its ability to demonstrate that its digital investments were delivering results, (and its chairman’s ability to stand up to the DfT?) seemed to give it a unique position to keep the digital taps switched on. I don’t think it is unrelated that LNER significantly outperforms equivalent TOCs on post-Covid recovery.

Transport for Wales had committed to a retail revolution before Covid hit, and were able to carry momentum through to deliver their new website based upon SilverRail’s platform.

Whilst TOC propositions stagnated, the third-party retail market rebounded, helped by the now universal acceptance of barcode ticketing. Trainline introduced automatic split ticketing capabilities, and refreshed the retail channels that it provided to TOCs such as Northern, CrossCountry and Abellio TOCs. The market also managed to attract two new entrants in this time – both big brands, each with a different angle.

Virgin Trains Ticketing

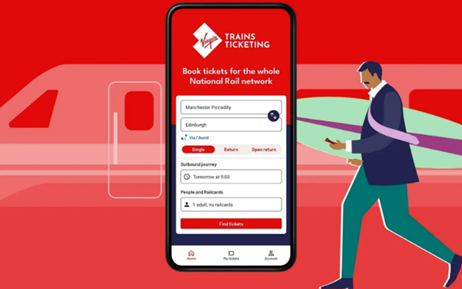

The first of these in summer 2022 was Virgin Trains Ticketing.

This would be the third proposition that Virgin had launched for online retail of GB rail tickets (following on from Trainline in 1999, and the Virgin Trains East Coast site in 2017).

This time, however, it launched as an independent, and integral part of the wider Virgin group, and specifically the Virgin Red loyalty scheme. The proposition promotes three key selling points:

- No Booking Fees

- Earn Loyalty Points

- Split ticketing

The proposition runs off SilverRail’s platform, and is a pure play app proposition (it had launched a few months earlier in beta as a feature of the Virgin Red loyalty scheme).

Figure 21: Virgin Trains Ticketing advert

Uber

Summer 2022 also saw the arrival of global mobility brand, Uber.

Uber had noticed the opportunity to diversify from private hire bookings, to become a full urban mobility proposition, with rail as a key part of that.

Uber partnered with Omio for their rail content, who in-turn leverage the Assertis platform for GB rail content.

The proposition was relatively low key until late 2023, when it was promoted by a significant marketing campaign, and blanket 10% discount.