Published on January 11, 2024

Like many others, I’ve loosely followed the Post Office “Horizon scandal” since it first appeared in the paper copies of Computer Weekly that used to land on my desk 15 years ago. Nonetheless, the ITV drama shone a light on it in a way that really hit home.

Inevitably a lot of the immediate commentary has been on justice for those involved, and getting to the bottom of how this specific case was able to happen.

Whilst others look at that, my thoughts have turned to the impacts outside of the Post Office domain, and closer to home. What are the future ramifications? Are there issues and weaknesses in our own systems and processes? Are we at risk of wrongly accusing people? Will our evidence be trusted where we correctly accuse people?

It is reasonable to think that in future courts will, quite rightly, be much more sceptical about relying upon computer evidence. I suspect we’ll frequently hear two simple questions:

- Can you guarantee that the system is bug free?

- Can you guarantee that no staff were able to remotely access the system?

The systems and procedural controls may well be much better than those illustrated in the Horizon case, but there will still always be that residual doubt. You might have immutable transaction logs, and procedural controls around remote access, but will a technical expert explaining these have any credibility?

I wouldn’t be surprised if this becomes a turning point in the ability to rely upon computer-based evidence. Even evidence such as photographs is increasingly unreliable given the ability to make virtually untraceable amendments, or to present entirely AI generated images.

Thinking specifically about transit, many areas could be impacted, ranging in both volume and value.

Similar to the Post Office, we also have a remote workforce where we expect the cash and the till to balance. That includes ticket office clerks, bus drivers and train guards. In many cases there will be remote access to those point-of-sale devices. The integrity of the data trails back from those devices to “HQ” varies. National Rail benefits from the third-party scrutiny brought by RDG accreditation, but this is relatively unique across the sector.

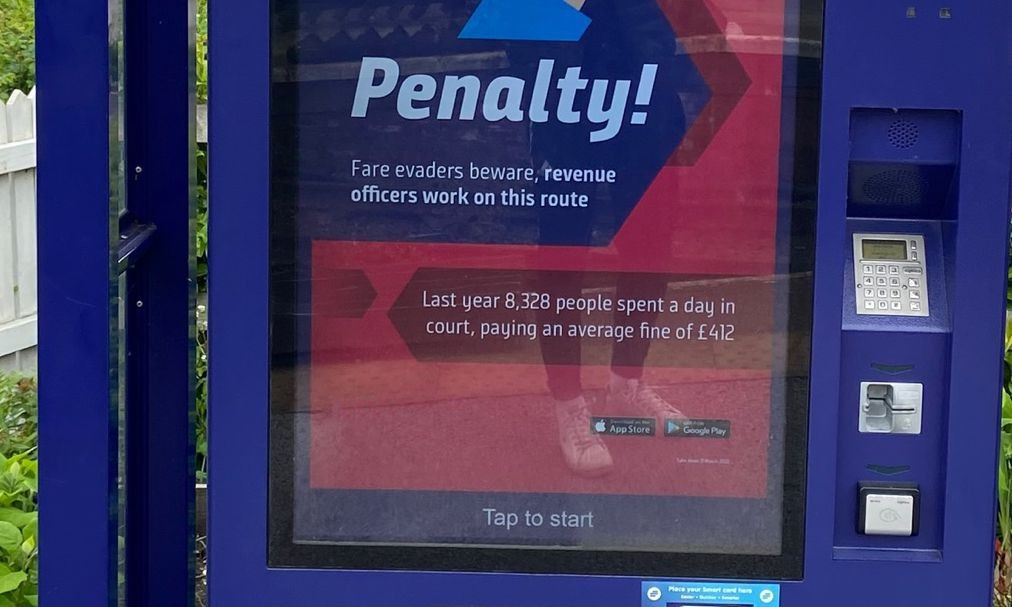

Transit is also a sector that both fines and prosecutes the users of its services, typically for ticket related fraud. Computer evidence often supports those prosecutions. Could that evidence now be called into doubt? Indeed, we should be challenging ourselves to doubt it!

To date, I suspect the risk has been relatively low – we’ve tended to rely on physical tickets (or the absence thereof). However, as we move to “account based ticketing” we rely upon computer records. How can we be sure that a customer actually did (or did not) tap their smartcard or phone on a gate? Are we sure that no one in the technology team could inject spurious scan or tap records? Are we sure that records can’t be lost by the system, or maliciously deleted by staff? How do we get that confidence from our supply chain?

Even if we are confident, how can we demonstrate that evidence if needed – both to our own boards and management teams, but ultimately in a prosecution? Would you feel comfortable to be the expert witness in the dock swearing that there is no way the system could be at fault?

Risks are often introduced when the use of a system evolves beyond its original design. To give an example, last year I was asked to look at the feasibility of using QR codes for “pay as you go” ticketing. The hypothesis was relatively simple: – we already get ticket scan records from ticket gates and bus ETMs when someone scans a QR ticket, could we turn that on its head and use it to charge people retrospectively? The answer was conceptually “yes”, but it required a step change in the level of integrity around scan records. Historically scan records were primarily (a) to prevent someone claiming a refund on a used ticket, and (b) to provide management information on usage. If the system lost a small percentage of records, it didn’t matter. However, for “pay as you go” this could result in a customer being fined for being on a train without a ticket, and the data integrity wasn’t fit for that purpose.

Finally, the case got me thinking about a relatively trivial, but nonetheless annoying, personal experience: Last year I received a £100 parking charge notice for a hotel car park. I’d paid for the parking via a mobile app subcontracted by the parking enforcement company but the parking enforcement company were adamant that I had not paid. I had a screenshot and other evidence showing that I had, but, to cut a long story short, they would not accept this as evidence – suggesting I had entered the car registration or location code erroneously (despite both being correct on the receipt that I provided to them). The parking enforcement company advised I’d exhausted their appeals process, and offered to settle the matter for £20.

I paid the £20, partly because I had my doubts that if let it go to court, would I be believed? It simply felt like it would be a lottery as to whether either side could prove it. I assumed it was a system bug and that some data records from the third-party app provider had for whatever reason not made it into the system of the parking enforcement provider. They would presumably assert that I was a fraudster that had “photoshopped” a receipt. I now wonder whether it could even be fraudulent on their part. It only needs someone to delete one data entry, or change a location code in a database, and my payment would no longer match the automatic numberplate recognition. Do performance incentives exist that might incentivise an individual to do this?

One thing that was very much in common with the Horizon story was the absolute belief that their computer was right, and nobody cared to investigate: I contacted the mobile app provider explaining the issue and asking for evidence that I’d paid, but they advised they were unable to intervene. I wrote to the hotel manager, they never replied. I wrote the hotel chain head-office, they never replied.

The Horizon drama paints a picture of a shambolic organisation and malicious practices. It’s tempting to see nothing in common with our own organisations and believe “it could never happen here”. I’d suggest, however, that its probably time to test that hypothesis, just to be sure.

Footnote:

Since publishing this article, I've had feedback that it's unhelpfully shining a light on transit ticketing, when there is no evidence of any problems in transit, and the context is very different to the Post Office.

For the avoidance of doubt, I have no reason to believe that transit has been unfairly accusing or prosecuting people, nor that there are any material faults in transit systems.

The article was simply intended to be thought provoking for those working in transit payments, many of whom have been discussing similar thoughts this week. Indeed from conversations with friends in other sectors this weekend, it seems like many sectors are having a moment of reflection.