2010 to 2015 was not just about mobile, it was about a growing maturity of digital skills and capabilities. For much of the period, this provided the income, to fund the still speculative investment in mobile.

Complex analytical models worked out the value of different search terms, and the likely conversion rate of different straplines and summaries to use in tailored bidding for online search results.

Advanced web analytics were giving a real-time view of customer behaviour on websites, tracking where customers arrived from, what they did, and where they dropped out.

Advanced analysis of customer data and buying patterns created much deeper understanding of the different needs and customer cohorts.

Email campaigns continuously tested new angles, new phraseology, and new subject lines to determine which performed best at re-engaging customers.

Third parties were very keen to place cookies based on customer searches. Knowing that you were a young person’s railcard holder, visiting Bristol in July, would allow a raft of tailored retargeting as you browsed elsewhere on the internet.

Supporting customers via social media started in an era when we still had to explain to management what social media was, and why we should be using it. Many in rail retail were early adopters of letting their customer support teams support customers via social media, when many other organisations still felt that social media should be the preserve of the PR department and carefully crafted generic responses.

(Just as an aside, credit to anyone who works in social media for a train company – I can think of few other roles that are the receiving end of such as sustained level of unpleasant abuse, whilst trying to help, and rarely being to blame).

‘A-B testing’ evolved into ‘multivariate testing’ and ‘conversion rate optimisation’ – presenting subtly different versions of a website to different control groups, so see which performed best, and progressively optimising the site design.

Restructured organisations and ‘new’ software development techniques saw moves into continuous integration, automated testing and continuous deployment – allowing changes to go live daily. Compare this to ten years previously, when software updates might be deployed four times per year.

Those without large digital marketing budgets looked for different routes to market. Notable was RailEasy and their “split ticketing” proposition. Split ticketing is where a ticket from A-B plus a ticket from B-C is cheaper than a ticket from A-C. It is an entirely legal way to save money on a journey, providing the train calls at ‘B’. This money saving technique allowed RailEasy to feature prominently in money saving websites.

Train companies, National Rail Enquiries, trainline and the other independents were passionately competing for customers. New digital capabilities were regularly coming online, and early and effective adoption would be key to keeping one step ahead of the others. Once again, this was an exciting and rewarding time to be involved.

Figure 18: trainline "Be Sensible" campaign launched in 2012

Cyber security

There were less glamorous aspects to contend with too. This period also saw the maturing of digital security standards, and in particular the Payment Card Industry Data Security Standards. Customer privacy concerns and looming GDPR regulation, also started to control some of the more intrusive use of customer data and retargeting. On one hand the shackles of 1990s software management processes were being removed, but a new set of guardrails being established for threats from the cyber era.

Knock-out Marketing

Whilst on the topic of cyber security, it is worth a brief diversion to note an incident that was not as it seemed.

One afternoon, the automatic monitor dashboard showing the system health go red. Sure enough, the website was unresponsive, so a P1 incident was declared and an incident team mobilised.

After a period of initial analysis, it became apparent that the website was under some form of distributed denial of service attack. Thousands of requests to load the homepage were hitting the site in rapid succession, from thousands of unique IP addresses. Security experts were mobilised to investigate and mitigate.

After much head scratching the problem was eventually traced to an unlikely cause, the business’s own marketing: At the time Google allowed online adverts to contain a “tracking pixel”. This is a web URL that would be loaded each time an online advert was displayed. This allowed digital businesses to see in real-time how many of their adverts were being served. In the configuration of the online adverts, the URL of the ad-tracking platform should have been put in this field, but instead someone had erroneously put the URL of the main website homepage. Every time an advert was served, it was causing the user’s browser to also make a request to the homepage, overwhelming the website.

Supply chain worries

This period also saw some supply chain worries.

Many online channels, including National Rail Enquiries and trainline used a journey planning and fares engine called IPTIS. This had been developed for trainline in the late 1990s, and since become widely used by many online retailers. It was owned for much of this time by Jeppesen, part of Boeing, a global giant that could surely be relied upon. There was therefore surprise and concern when it was announced that this division was being sold off, and if a suitable buyer wasn’t found, that the future was uncertain. Fortunately a buyer was found: SilverRail. This resolved the immediate worries, but the episode had spooked trainline, and SilverRail was also a competitor to it in the b2b market. This episode would catalyse trainline taking on the non-trivial task of building its own journey planning and fares engine. A complex undertaking, but one that would ultimately allow more innovation in journey planning – most notably the ability to offer customers split ticketing opportunities.

Another surprise from the supply chain came from Masabi. At this time the vast majority of train company mobile apps were supplied by Masabi. The move to mobile ticketing was progressing relatively quickly for the rail industry, but this was far too slow and bureaucratic for a nimble start-up. Despite their pivotal role in the formative stages of mobile ticketing in GB rail, Masabi decided to exit the market, and focus on urban transport in the US. For some retailers this fitted well with their plans to in-source this activity, for others it left them scrambling to plug the gap. Many simply ignored it, and hoped it wouldn’t happen.

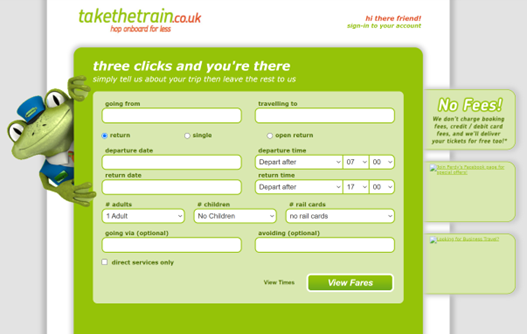

TakeTheTrain.co.uk

“Take The Train” was an online retailer from Click Travel targeting the consumer market. It launched in 2011 and ran until 2017. It was largely an ancillary channel, as the business primarily focused on business-to-business sales.

Loco2

2013 saw the arrival of another independent retailer, Loco2.

Loco2’s goal was to launch a low-carbon travel company, specialising in grounded travel, and the focus evolved into European rail.

Loco2 was acquired by e-Voyageurs Groupe, a subsidiary of SNCF in 2017, and rebranded as Rail Europe in 2019.

API integrations

One of the concepts that took hold in this era was the concept of making online retail platforms available via APIs - system-to-system interfaces - rather than just via a web front end.

The early uses for these APIs included travel management companies and online travel agencies, who already had booking engines, but simply wanted a pair of interfaces to "get fares" and "book fares". This allowed rail to appear in integrated booking platforms alongside hotel, air and car hire. Later, direct to consumer propositions (such as Loco2, Virgin Trains Ticketing and Uber) would be developed upon these type of APIs, reducing the amount of technical complexity that needed to be recreated.

The GB rail market is relatively unique. In most of the EU, and indeed globally, the national railway provides these APIs. This reduces the complexity of bringing a basic proposition to market, but limits the ability of retailers to innovate as they are constrained by the APIs published by the national railway.

In the GB rail market, however, third parties take the raw data and as a result the provision of APIs for search/booking inventory is a competitive market space with a choice of different API providers available, or the ability for retailers to build their own business logic. Online retailers such as Trainline and RailEasy diversified into providing their platform as a service, with others such as SilverRail being 'pure play' API providers with no real online presence of their own.

Interestingly, many players in the GB market bemoan the overheads of the GB approach, whereas many players in the EU market bemoan the inflexibility of the EU approach.