Published on June 19, 2018

Mobility-as-a-Service (Maas) is one of the hot topics of the moment – so here’s the first of a couple of ‘deep-dives’ into the topic.

What is Maas?

First, we should define what we mean by MaaS - as the label seems to be used quite liberally by many people trying to make their product seem a bit trendier.

I think the general consensus is that Mobility as a Service is the use of a portal (typically an app) to access and pay for transport services as required, as an alternative to private car ownership. This may be on a ‘pay as you use’ basis, or may have fixed price bundles. Whilst the focus tends to be on public transport in urban markets, conceptually there is no reason it shouldn’t apply to longer distance journeys and/or include modes not typically considered as public transport – and indeed you may even find car hire within the offering. In the near-term MaaS is mostly a portal to existing services, but the vision tends to assume over time that it will catalyse increased use of shared and ‘on demand’ services, which in due course may be autonomous vehicles.

A variety of factors come together to make the concept attractive:

- The ‘sharing economy’ and a wider trend away from ownership to buying services ;

- Ubiquitous connectivity, apps and associated technologies making it easier to find out about and pay for services;

- A reduction in the proportion of younger people learning to drive, and reduction in the role of private car as ‘status symbol’;

- The future potential for autonomous vehicles to fundamentally change mobility.

The mobility market

Before considering how the market may change it is worth understanding the current mobility market.

It is estimated that we spend in the region of £135bn per annum on personal mobility in Britain – to put that in perspective that’s nearly three times the defence budget, and about the same as total NHS spending.

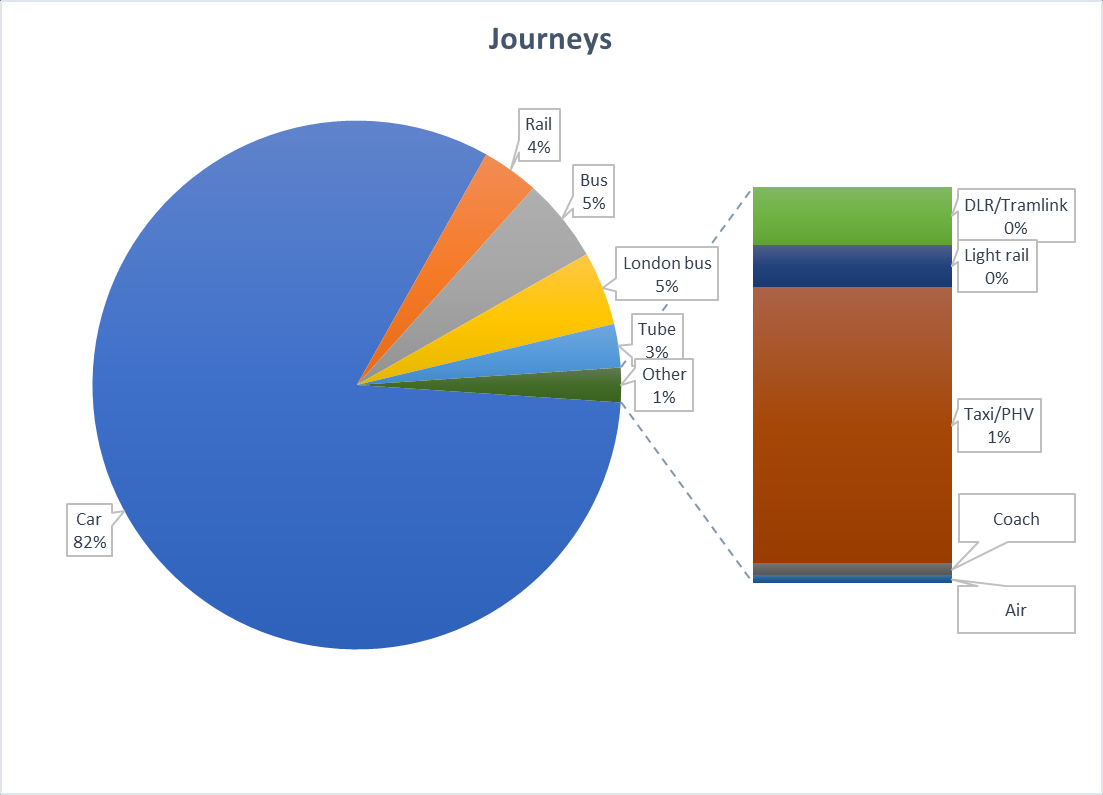

Just over 80% of all journeys are made by car – covering 250bn vehicle miles – at an estimated cost of ~£110bn each year. It is estimated that cars are parked for 96% of their life – not a great utilisation for something that’s roughly two-thirds fixed cost. It's not difficult to see why there is interest in applying an alternative more efficient model, and turning a slice of this cost into new revenue streams.

How will MaaS change behaviour?

Underlying the MaaS concept is the hypothesis that better provision of information, easier payment, and better product bundles (e.g. fixed or capped price packages) will entice travellers away from private car to using more shared and public transport. The MaaS proposition may be provided commercially, or by a local authority. The intelligence and connectivity of MaaS will allow a migration towards shared services and ‘on-demand’ services as opposed to personal ownership and fixed timetables.

The business model for a MaaS portal provider

The business model of a commercial MaaS portal provider (e.g. Whim, CityMapper, etc) has similarities with that of traditional travel agencies and travel management companies. There is scope to make margin from:

- Taking a commission or kick-back on the products/services sold;

- Charging the customer a standing charge and/or booking fee;

- Marketing income from transit providers to position their product favourably;

- Monetising market intelligence and data.

Value is created for the customer through:

- Convenience – helping the customer to navigate and find existing options;

- Catalysing the viability of new transport methods – e.g. shared and on-demand services;

- Discounts – using buying power to secure discounted rates with transit providers.

Whilst the overall business model is likely to include a mix of all of the above, the significance of different elements will vary somewhat by mode. Some modes may even need to be included as a ‘loss leader’ to make the package work. The challenge in the near-term is sourcing the data, the supply arrangements, and cracking the journey planning conundrum - but over time this may increasingly be about brokering supply and demand, to balance customer needs and revenue opportunities.

A local authority lead MaaS proposition may be less focused on profit, and more focused on issues such as managing congestion, air quality, whilst stimulating economic growth and social mobility.

The key threat to MaaS portal providers appears to be the big players, such as Google and other digital assistants. If these develop very smart journey planning algorithms with comprehensive coverage of modes and services, integrated with other products they offer, it may be difficult for dedicated MaaS portals to retain sufficient volume. It’s not difficult to envisage a model akin to Google’s “PPC” advertising model, where transit providers bid to fulfil mobility needs. In due course, Google’s own autonomous vehicles could be the default option that it promotes.

A risk for rail

MaaS appears to be a threat to rail’s market share, and revenue per journey. Whilst I don’t subscribe to the doomsday scenario of MaaS + autonomous cars resulting in the end of the rail network, the impacts on demand could be material nonetheless.

Rail has benefited over the past two decades from being relatively good at providing information about services. Stations don’t move, and published timetables and routes are often well known. The National Rail Enquiries telephone line used to be the busiest phone number in Britain until its website took-up the majority of the enquires. Rail has no doubt benefited from the fact that getting information about alternatives such as bus and coach has simply been too difficult. As other modes become more accessible through MaaS portals, rail will lose much of this advantage. MaaS services may also help passengers make better ticket choices, not just buying the same day returns from the ticket machines, so even where there isn’t modal change, revenue might drop.

To benefit from MaaS, rail needs MaaS to succeed in generating net migration away from car to public transport. Not engaging, or passive engagement, is unlikely to make the MaaS threat go away.

On a more positive note, rail already has an established track record of allowing third parties to promote and sell its tickets. Whilst rail systems may be complex – there is at least a single point of integration and intermediaries can be used to solve much of the complexities. The advent of mobile ticketing has provided an alternative to high fixed costs of ticket collection/delivery, and which should integrate well into a MaaS proposition.

There’s no technical barrier to joining the party – the rail industry needs to find a way to ensure that the net migration to MaaS more than compensates for lost revenue and lost patronage to other modes – but a slow regulatory structure, and complex fixed infrastructure won’t help.

A mixed outlook for bus

Whilst aspects of MaaS have in isolation already cannibalised the bus market (e.g. Uber) a more comprehensive MaaS proposition could have a more balanced impact – but it needs bus operators to have foresight and a willingness to risk change.

MaaS portals will improve awareness of bus services. At present knowledge of bus networks by non-users is limited, and few even know where to go to find out. Making public transport information easily accessible through a MaaS portal will increase awareness of bus journey opportunities. Logic within MaaS portals could also be able to eliminate some of the negative aspects of bus experience (such as standing in the rain for a cancelled service or one that is too full to board).

There are key challenges for bus operators though. It’s a low margin business that mostly sells its services at the point of use at a low marginal cost. There’s no single source of fares information, and the only universally accepted ticket type is an ITSO smartcard. It’s hard for a MaaS portal to even give a first-time customer a ticket.

Current bus fare structures may also be a hindrance: In general (outside London), single/return fares offer fairly poor value for money – with best value only available on weekly single operator products. However, in a MaaS portal, a user might be comparing the cost of an individual journey by private hire vs by bus, and bus may simply appear too expensive on a per journey comparison – particularly for small groups of passengers.

Taking a strategic approach, bus operators could potentially develop partnerships with MaaS portals to understand demand that’s not currently served by bus, and target new services towards them. Unlike rail operators, bus operators have more flexibility to change their network (but this may be at the expense of having a greater number of smaller vehicles, and with the risk of drifting towards becoming a minicab firm with high overheads).

MaaS portals have potential to provide the critical mass that’s required to make true demand responsive services and/or routes work. It’s not surprising therefore that we’ve seen the arrival of Arriva Click, Vamooz and Go-Ahead’s ‘Pick Me Up’ propositions. There is a risk however that in future MaaS portals simply broker the demand to several competing operators, holding down margins for the operators.

An opportunity for Coach

Coach often seems a forgotten part of the public transport network, and is relatively small (about 2% of the volume of the rail network). Whilst coach will struggle to compete with long distance rail on journey times, it has a much lower cost base, and can much more readily adjust its network to meet demand (examples being Zeelo or Sn-Ap).

MaaS could drive some significant growth in this area, and as MaaS evolves from being an urban centric proposition, it could play a key role in aggregating the demand to make it work. This isn’t just about students and low-cost holidays – but could cover mid-distance commuting markets, and much more comprehensive event/attraction coverage. Whilst many people will continue to be willing to pay a price premium for rail over coach, this is likely to further erode the price sensitive end of the rail market.

Not a great outlook for Taxi / Private hire

Uber and alike have been seen by many as the leading edge of MaaS – but behind the headlines it seems to have created more losers than winners. Whilst the overall impact has generated volume - traditional mini-cab firms and taxis have lost business, the number of drivers has increased and there has been a deflationary pressure on fares and individual driver earnings. Furthermore, a common assumption appears to be that drivers are just an interim component ahead of autonomous vehicles – so more changes ahead.

In many ways this is a good illustration of the wider impact MaaS might have: growing volume, but at the expense of driving down margins, as it becomes easier to migrate to demand to service providers willing to work for a lower margin.

Even Uber themselves may become an unnecessary tier in the ecosystem, if MaaS portal providers find alternative ways of finding supply (hence it is not surprising to see Uber diversifying towards becoming an MaaS portal itself).

Other players

Bike hire, and specifically dockless bikes, appears likely to grow in a MaaS world – albeit as players clamour for market share – will we see a repeat of China’s overstocked bike mountains? (The thread of an imbalance between supply and demand runs throughout MaaS).

Car-clubs – essentially a more convenient and high-tech form of car-hire (E.g. ZipCar, Car Club ) should do well in urban and sub-urban markets – albeit the feasibility for the 17% of the population that live in rural areas is more challenging. (Albeit as a passing note, it’s interesting to note how agriculture has moved significantly to the sharing economy already, with family owned 30-year old combine harvesters being set aside, replaced by bigger and smarter machines rented by the hour).

Car-pooling / ride sharing (e.g. Blah Blah Car) still seems to be hindered by social acceptance rather than capability, with Britain lagging in the adoption stakes. MaaS might help here, tipping the balance to the mainstream, but it might also remove the supply as some of those lone drivers abandon their cars (nb: this is a market already constrained by supply). And for those who are willing to let a stranger do the driving, you could swap the car for a private plane with Wingly – which will probably only ever be a niche option before personal drones eliminate the market completely.

The role of car-parks, at least commuter car-parks, may change somewhat. There will still be a need for vehicles to stay somewhere – but the long-stay market should see reduced demand as vehicles are shared more, and idle less.

Impact of local authority policy

Many local authorities are keen to influence how MaaS contributes to their local issues and opportunities. At a basic level reduction of private car use is usually regarded positively; a migration of passengers from bus and train to new forms of private hire vehicles is not desirable; but growth of private hire vehicles for the ‘last mile’ is probably acceptable. Local authorities will need to consider their position on policies such as the sorts of vehicles/services allowed to use ‘bus lanes’ through to whether free bus travel for certain demographics is replaced with some sort of ‘personal transport account’ which can be redeemed across a wider variety of services.

Local authorities could even seek to be the MaaS portal provider for their area – albeit it’s hard to believe many would be able to sustain the investment and innovation to out-run Google and others (particularly when MaaS will work best when it is an integral part of a wider digital assistant).

Energies might be best focused on attracting providers to prioritise their area, and helping ensure that passenger needs are met. There could be a specific need for local authorities to intervene to protect rural areas – as it is conceivable that commercial MaaS operators concentrate their efforts on the populous urban areas where propositions are easier to establish and demand is greatest.

Private car ecosystem

The impact on the private car ecosystem will clearly be huge, and too extensive to cover here - particularly considering the additional impacts of the move towards electric vehicles and autonomy. From manufacturers, dealers, servicing/repairs/breakdowns, fuel, service stations, financing, insurance, through to road building - that £135bn currently supports a lot of businesses. If we spend less time in our cars, that may even be another nail in the coffin for local radio.

Summary

We are in a period of significant change in personal mobility – even the underlying needs for mobility are changing with emergence of home working and improved technology.

The winners and losers are hard to call – particularly given that much of the model seems very sensitive to oversupply, and could simply become a high volume negligible margin business. It might be that whilst the majority invest in autonomous connected vehicles for urban markets, that the best returns come for those that buck the trend and do something less glamorous.

About the author:

Richard Rowson is a freelance consultant at f17.co.uk focused on public transport ticketing, information and fares.