After the initial post-privatisation excitement, by 2002 the rail industry was quite simply in a mess. The world of online appeared little better. The dot.com bubble had burst in 2001, and seemed to be followed by a steady stream of bad news and stories of overhyped promises.

However, despite that context, it was an exciting time for selling train tickets online. Both thetrainline and Qjump displayed an entrepreneurial hunger to rapidly grow their sales volumes and customer databases, whilst at the same time learning to cope with the challenges that the rapid growth brought.

Arm’s length move

Prior to 2002, thetrainline.com had been incubated within Virgin Trains, and Qjump within National Express Group (primarily in the Midland Mainline business).

This changed in 2002 as thetrainline.com was demerged from Virgin Rail Group, and Qjump established as its own legal entity. This was more than just a paper-change, it brought with it strengthened management teams, a mandate to grow in their own right, and a necessity to deliver a return on investment.

Although management teams were picked for their expertise, many board members were not digital natives and the levels of understanding varied. A handful probably still felt that online was a passing fad that they had to play along with due to shareholder expectations. They had no real way of knowing whether the detail of what the teams were doing was right, and at times board meetings could be rather surreal and abstract. There was support, but at the same time the businesses were very much on trial.

Acquiring customers

A linchpin to success would be acquiring customers – with the main focus at the time being those customers planning longer journeys in advance.

There was no playbook for digital marketing, so the businesses had to think for themselves of how to attract, convert and retain customers. This broadly broke down into five themes:

- Signing-up train companies to run their branded sites

- Consumer marketing of own brand channels

- Customer data

- Other partnerships and relationships

- Business travel

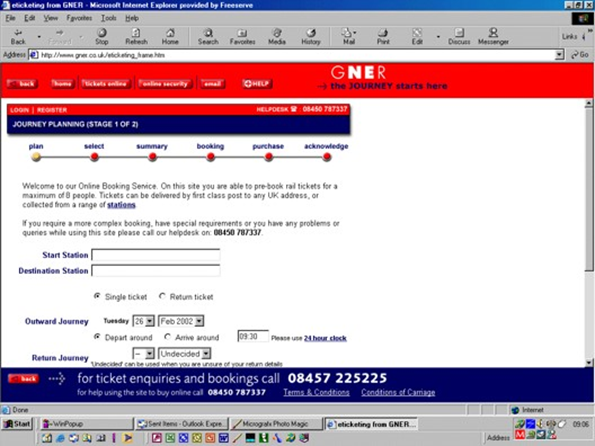

During this period, relationships were established with most train companies. With thetrainline.com powering Virgin Trains, South West Trains, and Great Western. Qjump meanwhile signed up GNER, GoAhead and Arriva, in addition to the nine National Express train companies (Midland Mainline, Central Trains, Silverlink, Gatwick Express, Scotrail, WAGN, c2c, Valley Lines, and Wales & Borders).

Figure 3: GNER online booking engine powered by Qjump

Consumer marketing combined traditional offline marketing, with more experimental online marketing. Although thetrainline and totaljourney had enjoyed multi-£m marketing budgets for launch campaigns, by 2002 the purse strings were much tighter. Qjump stretched its limited budget by leveraging relationships with other National Express businesses: vinyl wrapping a train and several buses, along with plastering almost every National Express train window with advertising stickers.

Figure 4: A class 170 train wrapped in Qjump advertising

Online marketing was not about social media and search engine optimisation, but more about banner adverts and affiliate schemes (Ask Jeeves generated more referrals in 2002 than Google). Most marketing was primarily trying to drive behaviour shift from ticket offices and telesales to buying online, and competition between the different online sites was secondary.

thetrainline required users to register to see fares information, which no doubt helped with driving up its registered customer count to 7m by the end of 2003. Qjump only required registration to make a purchase, acquiring 0.5m registered customers by the same time. This was an era before PECR and GDPR, when automatic opt-in to marketing was still commonplace, and selling lists of customers between organisations was still a source of both income and new prospects. It was also a time when the kudos for having a large customer count somewhat exceeded the value realisable from it. In practice many customer records were duplicates, or abandoned addresses as customers swapped internet service providers and changed their addresses.

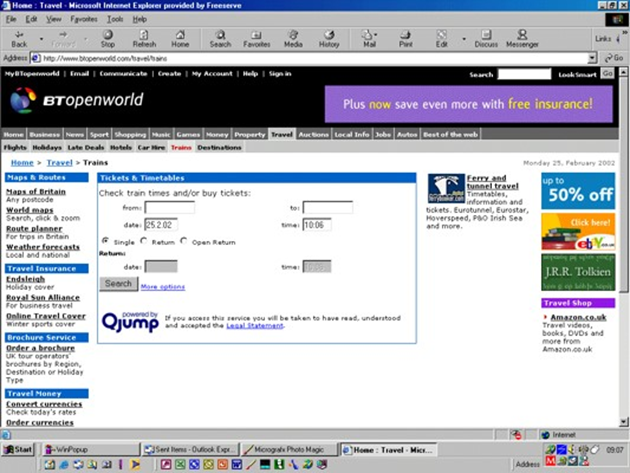

Another area of focus was on ad hoc partnerships and product placements. Internet service provider landing pages were important places to feature, as many users still used these to find their way around the internet. Other partners included Expedia, Multimap, Teletext, Telegraph.co.uk, the London Tourist Board and Thisislondon. Qjump partnered with Hilton to create “Hilton Rail Breaks”, and later thetrainline would develop “seeyoumonday.com” as a short-breaks packaging site.

Figure 5: Qjump providing the train search capability in BT Openworld portal

Both businesses also built a portfolio of business travel accounts – albeit in the main these were in the call-centre domain rather than online, with faxed order forms still commonplace. Qjump launched a self-service business travel portal for small businesses, whilst thetrainline targeted larger businesses with bespoke solutions. Prominent colourful stands at the Business Travel Show shouted about the arrival of online rail bookings.

Product and technology

Acquiring customers and growing volumes was just part of the equation. There was still a lot to be done on the product and technology front. This covered competing objectives including:

- Making the proposition more attractive to customers

- Making the business more efficient to operate

- Supporting more of the long tail of quirky ticket types that didn’t retail correctly online

- Keeping up with the pace of technology change

- Implementing mandatory industry changes as the industry replaced and overhauled the systems inherited from British Rail.

Ticketing

A key focus throughout the 25 years has been on making it easier for customers to obtain their ticket, and this was very much the case in 2002 too.

When thetrainline launched, all tickets were still sent out by post, with a choice of regular post, or Next Day Special Delivery, and this was still the prominent fulfilment method when Qjump launched too.

This diluted the customer proposition, needing at least 48 hours to book. It created operational issues of getting all the tickets into the correct branded envelopes and dispatched in the post. It created cost, and for much of the time the threat of postal strikes threatened to suspend the business entirely. Ticket printers that worked adequately in ticket offices, failed under the continuous throughput of fulfilment centre operations. “Just in time” delivery of ticket stock was often “just too late”, and freshly printed blank ticket stock had to be “aired” on radiators to finish the drying process before it could be loaded into printers. There was a philosophical divide as to whether customers should be issued with credit card size tickets that fitted conveniently in purses/wallets and worked ticket gates, or with airline style “ATB2 tickets” that looked more worthy of the £100 the customer had parted with. Fulfilment was an Achilles heel.

The solution at the time was what retail now calls “click and collect” – but for the rail industry was known as “ticket on departure” or “TOD”. This came in two flavours – “CTR” and fax.

“CTR” – or Customer Transaction Record – to give its full name, involved writing the booking details to a central industry database, and giving the customer an 8-letter collection code. The customer could collect from the new generation “Fast Ticket” self-service machines at approximately 30 stations, with the back-up option of the ticket office. An evolution of this approach still exists today.

It sounds conceptually simple, but in practice had many rough edges. The self-service machines couldn’t always issue the same tickets that the website could sell. Datacoms to stations could cause printing to fail part way through an order, locking the transaction and leaving the customer with an incomplete set of tickets. But by far the biggest problem was the financial reconciliation: The rail industry tracks ticket issues, and expects the payments taken to match the tickets issued for each location: A basic audit principle that ensures that rogue ticket office clerks don’t pocket the money from their station. That concept worked fine where sale and issue happen at the same place at the same time, but TOD created the concept of payment being taken by one entity, and tickets being issued by a completely different entity in a different location, often many days later, sometimes in a completely different accounting period. Sometimes customers would not travel, and hence wouldn’t collect their tickets, but payment had still been taken nonetheless. For several years this was managed via spreadsheets, with lots of manual intervention, before finally moving to a more automated system, which evolved into the one still operated today (but nonetheless one that took lots of manual management to keep the finances in order). There was, initially, no national agreement, so agreements had to be struck with each train company separately to access their machines.

If that sounds primitive, Qjump also supplemented this with something even more basic. Qjump leveraged its relationships with train companies to establish a process whereby for stations without self-service collection, orders were received online and faxed to station ticket offices. The stations would then manually key the booking into the 1980s ticket machine at the ticket window, and put the tickets in a shoebox (or similar) until the customer came to collect them. Those familiar with modern data security standards such as PCI-DSS for bankcards would be appalled – the entire booking, journey, customer details and bankcard details all printed in plain text on the fax. It may have been low-tech, but this primitive solution gave Qjump access to hundreds of stations not available via the CTR process.

This process was also used to mop-up “lost in post” bookings. If there wasn’t time to post replacement tickets, then the retailer would arrange for them to be issued at the station for the customer to collect. This involved another manual financial process known as “transfer vouchers” (kind of like a cheque in reverse) which the station would write out by hand and send to a central processing unit to be remunerated for the cost of issuing the replacement tickets.

It is worth noting at this point that retailers carry the cost for lost tickets, having to pay the industry for both the original tickets, and the replacements ones. Lost in post claims were surprisingly high – well above what Royal Mail experienced with other customers. Later analysis would establish that many were not lost, but fraudulently claimed as undelivered to obtain a second set of tickets for a friend or relative. A kind of unofficial, “buy one, get one free” proposition. This would lead to some addresses being “deny listed” for a while (mostly student halls of residences), in turn resulting in a Transport Select Committee grilling on the alleged discrimination this caused.

Journey Planning

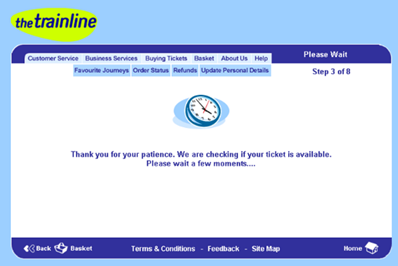

Alongside ticketing, the other key challenge was journey planning, fares and availability. At the time of thetrainline’s launch in 1999, even without the challenges of GB rail fares, this was a computational challenge: evaluate all relevant journey opportunities, evaluate all possible fares, map which fares were valid on which services, and check the industry mainframe for ticket availability. This required taking overnight datafeeds and optimising them to allow quicker run-time results. Nonetheless the search still required a “please wait” page and many seconds before showing results. Qjump took a different approach, quickly showing customers train times, and drilling down to show fares and then availability.

Figure 6: After logging in, customer were presented with a "please wait" screen before seeing fares

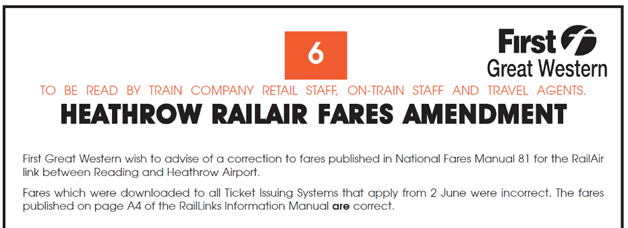

Giving accurate results was a key challenge. There were two key aspects to this. The first was the simple fact that the rules for establishing ticket validity were (and are) complex. The second was that the industry was not used to its data being used directly by computers and customers. Previously ticket office clerks or call-centre agents were expected to be trained and knowledgeable, and address gaps and errors in the data. Often rules about when tickets could be sold weren’t codified into data, but were described verbosely, and included in retail briefings faxed to stations. This required additional reference data to be created and maintained, and sometimes for data to be corrected after receipt from industry data. It took a decade to reach a maturity where it was recognised that products for sale had to be accurately represented in industry data, and that you couldn’t simply blame the retail systems for showing what was in the data.

Figure 7: Amendments to fares and restrictions were often circulated in NewsRail Express

Outside of the limelight of online, thetrainline and Qjump between them had over 1,000 contact centre agents, and for much of the initial period, this was still the majority of the volume. thetrainline’s operations were outsourced to Vertex in Dingwall and Edinburgh, whereas the Qjump team were in-house in Sheffield. These were sizeable operations with their own challenges, and for much of this period, feeling the full brunt of the disruption going on in the wider railway. Agents were expected to be able to explain the T&Cs of a “Virgin Value 7 Day Advance Return” one minute, and the next explain how to “enable cookies” in a Netscape browser. Online chat support was piloted, because customers couldn’t be on dial-up internet, and the phone to a helpdesk at the same time. In parallel to the online side of the business, National Express was also consolidating its various rail call-centres into Qjump in Sheffield. This meant the team had to learn about the geography and tickets of parts of the rail network from North London, Wales, Midlands and Scotland.

National Rail Enquiries

Whilst thetrainline and Qjump focused on online sales, National Rail Enquiries (NRE) was developing its online presence focused on information. When Railtrack went into administration, it took over responsibility for providing the basic timetables only journey planner still used by many, whilst spinning up work to provide a full times/fares/availability service, live running information, along with information about engineering work, unplanned disruption, stations, products and other ancillary information.

From March 2003 it contracted thetrainline to provide journey planning and fares (Qjump also bid but was unsuccessful), and in June 2003 launched online live departure boards. In the first year from taking over journey planning from Railtrack volumes doubled to 40m per annum (albeit alongside a still sizeable 60m telephone queries). NRE would prove to be a key source of referrals to thetrainline, Qjump and the train company booking engines.

Two transformative years

The thetrainline and Qjump years were an intense and formative period. For those involved it was exciting and exhausting in equal measure. The dot.com bubble may have burst, but the online world was still evolving rapidly, still very much in the limelight and much was uncharted waters. You had to think for yourselves and got to invent stuff in the process. It was far more rewarding than implementing decades of best practice defined by those that had gone before. What was lacking in budget, was made up in entrepreneurial drive and creative thinking.

The step change and pace of change in online capabilities offered to rail customers over those two years has never been matched since, particularly when NRE’s work on information is included.

Compare that to the two years since DfT announced its £360m investment in rail ticketing back in November 2001. Having worked in both, I’d call out two key differences:

- Qjump and thetrainline were empowered to make decisions, and to take an element of risk getting there. There was scrutiny and no blank cheques, but only really two tiers of decision making: the management teams and the board. Most time was spent doing, and relatively little time on business cases and PowerPoints.

- The businesses’ continued existence, the ability to deliver the next stage of its aspirations, and ultimately the jobs and reputations of the team depended upon attracting and retaining customers.

By the end of 2003, the industry was also starting to recover from the collapse of Railtrack 12 months earlier. Operational performance for the last quarter of 2003 was the best for four years. Patronage was recovering. Online sales growth was strong: 20% of Intercity journeys were being booked online; Qjump volumes were 400% up on the previous year; thetrainline was boasting 7m registered customers. Both businesses operated profitably, before interest, tax and depreciation. Home internet access continued to grow with nearly 50% of households online, and the move from dial-up to broadband was underway. The prospects for 2004 looked strong.