Published on January 30, 2019

Ask people about successful innovations in transit ticketing, and Oyster and contactless is often top of the list.

That’s not surprising. It’s a very convenient proposition, with the assurance of a best price guarantee. No longer do you need to spend time buying a ticket, nor do you need to know what your travel plans will be, and hence what ticket you require.

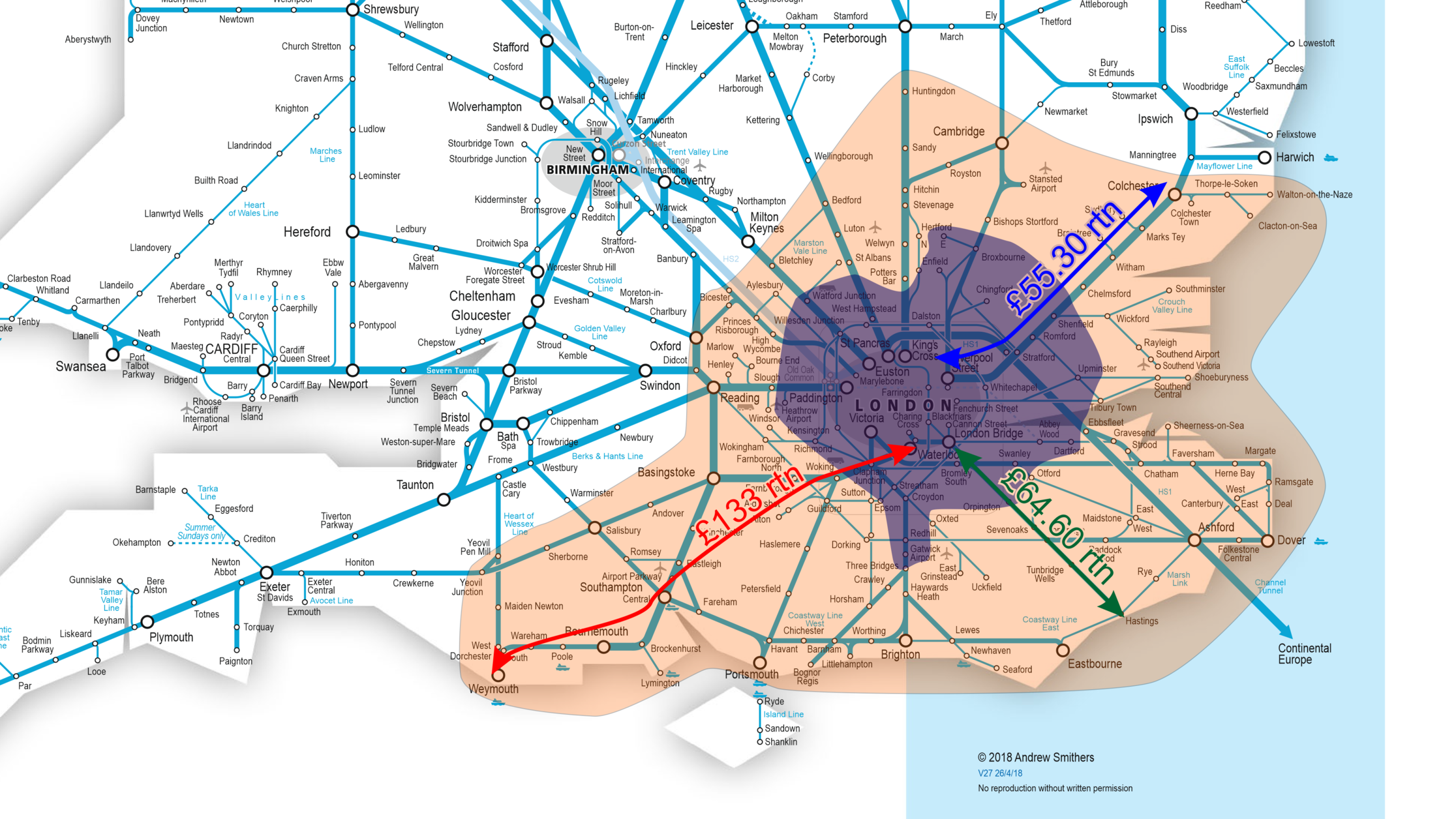

It’s not surprising therefore that there has long been a vocal lobby calling for the same approach to be taken to National Rail ticketing – specifically the simplicity of tapping in and out with a contactless bankcard. Transport for the North is procuring a solution for cities of the North, and more recently RDG and others have started promoting a scheme for the South East, covering the area from the south coast as far west and north as Weymouth, Reading, Cambridge and Colchester.

Such a concept will inevitably resonate well with customers, and therefore it’s not surprising that many people and organisations seems to have hopped onto the PAYG bandwagon, proposing ever wider coverage. However, I think we need to look beyond first order customer preferences, and consider whether PAYG really is the panacea that it is often presented as.

What is it that people like about contactless in London?

Tapping, capping and good value.

Tapping is a convenience proposition, no need to spend time buying a ticket.

Capping is a flexibility and value proposition, assurance that you’ll pay the best value fare for the combination of journeys, and no need to know in advance what those journeys will be.

This is supported by the fact that, generally, London’s fares are considered good value.

When residents of places like Epsom demand an extension of “Oyster” it’s all three that they want, albeit what they will actually get is just the first two. Nonetheless, two out of three is a good start.

What’s not to like?

There’s no disputing that contactless works well for many people.

The two main limitations are:

- You don’t know what you are going to pay until you’ve paid. Given the relatively low level of TfL fares, this isn’t a problem for most people with average earnings or more. You might not know the exact fare, but you know it’s comfortably less than £10, and trust TfL to get it right.

- There’s no customer interface, and therefore no opportunity to tweak you travel plans. Over the years, self-service ticket machines have been widely criticised for selling a full fare ticket at 09:15, without advising a customer that by delaying their journey by 30 minutes they could pay significantly less. Self-service machines have started to get much better at providing such information to customers, but contactless puts the onus back on the customer to know when peak-time finishes. This isn’t a major issue in London, as the standardised 09:30 start of off-peak is well known and easy to communicate.

What are the characteristics of London that have made contactless successful?

- A zonal fares structure that is widely understood, having been in existence for ~ 30 years;

- A ‘maximum fare’ that’s an effective deterrent to failing to tap-in/tap-out, but not disproportionate if you make a genuine mistake (for most of the network it’s £10.50);

- A price level where most journeys cost less than £10. As such many customers either know the price beforehand, or do not care about the exact price;

- A mostly gated network, reducing the risk of forgetting to tap-in/tap-out;

- A simple two-tier peak/off-peak structure, with harmonised peak/off-peak timings;

- Relatively few scenarios where the route taken impacts the price to be paid.

Many of the above points apply to other urban transport networks, such as those in Liverpool or Tyne & Wear, so it’s absolutely right that these areas are considering implementing similar schemes.

Why not extend to the whole of National Rail across the South East?

Before explaining the issues – I should explain my motives. This isn’t some sort of warped desire to preserve cardboard ticketing and indefensible fares anomalies. Ticketing and fares needs an overhaul, but not all markets are alike, and therefore a solution that works well in one market, doesn’t necessarily fit another. Indeed, in trying to scale contactless to such a wide area, the simplicity and trust that has made it so attractive, could be destroyed. Technical capabilities and customer expectations move on with time - copying a scheme that's already 10 years old isn't looking to the future.

Let’s look at the characteristics of the area proposed by Rail Delivery Group:

- A largely point-to-point fares structure, where individual journeys can cost in-excess of £100, and many journeys cost £40 - £60;

- A largely ungated network outside the urban core, that would presumably rely on platform validators (and therefore increased risk of forgetting to tap);

- Wide variety in peak/off-peak times, that reflect a genuine variation in the times that there is demand for travel (it’s off-peak for 7am departures from Weymouth!)

- Fares that vary upon route taken (e.g. cheaper if avoiding central London, or premium for HS1 services)

Without a radical change to the fares structure, that’s a pretty unattractive customer proposition:

- I don’t know what I’ll be charged before I start my journey, and it might be £100;

- If I accidentally travel 10 minutes too early, I might pay £50 more than waiting for off-peak (whenever that happens to be);

- If I make a short hop a few stops up the line, I might forget to tap out and get a £100 maximum fare (because I *might* have travelled all the way to Colchester).

A couple of years ago, I asked people in Sheffield to consider three propositions:

- ‘Travel anywhere in South Yorkshire, tap in and out, and you’ll never pay more than £7.50 per day’

- ‘Travel anywhere in Yorkshire, tap in and out, and you’ll never pay more than £30 per day’

- ‘Travel anywhere in the North, tap in and out, and you’ll never pay more than £130 per day’

The first option had the widest appeal. Even with the second option, most people were stating that they would want to know what the journeys were going to cost before they made them.

So surely the answer is to radically simplify the fares too?

In fairness, I think all those advocating a large PAYG area have stated that fares simplification is necessary. That’s an easy populist statement to make, and it’s easy to get first order support at focus groups. But focus groups and vox pops tend to only consider the first order impact.

Let’s look at a few specific examples:

- Peak / off-peak times: Across the South East these vary significantly – because local markets and demand vary. It sounds appealing to apply the blanket ‘off-peak for journeys starting at 09:30’ to everywhere – but that’s not appealing if you currently get the 06:55 off-peak departure from Weymouth, that suddenly becomes reclassified as a twice as expensive peak-time train. You might solve a fares complexity, but create the anomaly of lightly loaded trains being classified as peak-time services.

- Zonal fares: Whilst you don’t absolutely need zonal fares to make PAYG work, it is a much more attractive customer proposition with the assurance of an unlimited daily use fare, such as the London Travelcard fares. But zonal fares create price anomalies, particularly for journeys that go through a concentric fares structure and back out the other side, which in turn create ‘split ticketing’ issues.

- The role of train specific ‘Advance’ fares: One of the big trends over the past two decades has been the growth of cheaper ‘Advance’ fares. These have driven up patronage on off-peak services in particular. This is good for passengers and the railway. It allows more frequent off-peak services to be sustained, it makes more cost effective use of fixed price assets, and it gives those with flexibility of their travel plans a lower cost travel option. In a world of contactless, the customer potentially sees two contradictory value propositions:

“Book in advance online to save”

“Just turn-up, tap and go, best fare guaranteed”

- Either of these is potentially correct, depending upon the precise circumstances. Whilst it’s tempting to state that scrapping Advance fares will solve the problem – some serious consideration is needed on the second order impacts of such a recommendation.

Even if fares are simplified, there remain many conceptual challenges:

- What penalty do you charge people who forget to tap-out? It needs to be an effective deterrent for someone making a £100 journey, but not punitive for someone doing a £5 local hop.

- Do you keep the proposition simple, or make it more comprehensive supporting first class fares, railcards, concessions, etc?

For the avoidance of doubt – I’m not saying that fares reform isn’t needed. It is. But it is a complex topic with widespread impacts, and forcing a particular fares strategy to fit a particular ticketing vision, might have undesirable consequences.

Are you advocating that we stick with what we’ve got?

No. Change is needed. We can learn from successes elsewhere, but also be mindful of the differences of different markets. We should recognise that capabilities have moved on a lot since Oyster was specified, and by the time we launch propositions customer expectations will have moved on too.

I find it ironic that on one hand Government has been sponsoring pilots of ‘gateless gatelines’, but at the same time appears poised to promote a scheme based on physical taps of contactless bankcards. Surely a key point of innovation pilots is to feed those insights back into the future vision?

I think a key part of setting out the vision is to separate the concepts of ‘tapping’ and ‘capping’. Capping is a great proposition for customers, and it’s got long-term value for solving a real customer need. Tapping is a transient solution using last year’s technology – it may have a part to play for a long time given the slow lifecycle of infrastructure, but it should be just part of new solutions, not an exclusive part.

In the medium term, mobile apps can offer the best of both worlds.

With an app, customers can choose how much information they want. If you know your journey and fares, just use location awareness capabilities to ‘virtually’ tap in. If you’re uncertain, you can check fares, or even buy a specific journey as you do today, including Advance fares. You shouldn’t be excluded you from capping, if you buy more journeys during the course of the day, you should be entitled to the same caps as those customers paying with bankcards. Mobile provides a route to 'gateless gateline', location awareness, and wider bundling with other mobility services.

There’s a potential social injustice of restricting capping to only being available via bankcard tapping. It means that those who are least price sensitive get the benefit of caps, whereas those watching the pennies, those who desire certainty of what they are paying for a given journey, miss out on capping and potentially pay more. That’s wrong.

In summary

- Contactless PAYG using bankcards is great for well-defined markets, but it’s not a panacea for all journeys and all customer needs;

- Tapping and capping are separable concepts - much of the perceived benefit from PAYG is actually attributable to capping – and capping can be offered across a range of channels;

- Scaling PAYG to cover large geographies could destroy much of the trust and simplicity that has made it successful;

- For many journeys passengers want to know what it will cost before they travel, and will adjust their plans based on the cost. Excluding those who are most price sensitive from capping is morally wrong;

- Fares simplification is needed – but the over simplification needed to make bankcard PAYG work across wide areas will have detrimental second order impact for passengers and industry income.

- Capping when combined with mobile apps offers the best of both worlds, allowing customers to make informed choice on the cost of individual journeys, with the assurance of a daily cap.