Split ticketing - a quick guide to what it is, why it happens, how fixing it isn’t without its own issues, & how fares simplification may increase it

June 26, 2025

If you get into a discussion about saving money on GB rail tickets, it won’t be long until you hear about the concept of “split ticketing”.

This is where it is cheaper to buy multiple tickets for your journey, instead of one ticket for the end-to-end journey.

For example, instead of buying a ticket from A to C, you buy one from A to B and another from B to C. It’s perfectly legal, providing the train that you are travelling on stops at the station where you have split the tickets. There’s no need to get off the train, albeit you might have to change seats.

Some retail apps and websites automate the process of identifying split ticket opportunities, and automatically offer these as cheaper travel options to customers.

It is often held out as an example of the illogicality of the GB rail fares system.

Over the years I’ve been asked to help PR teams write justifications defending it, or to write plans for others to help irradicate it. In practice, neither is practical.

Losing revenue?

There can be a simplistic assumption that split ticketing is losing the rail industry money, and that if it was eradicated, customers would revert to paying the full fare.

But this is over simplistic, and ignores that demand varies in response to the price, particularly given the rail industry now makes the majority of its revenue from leisure journeys.

The impact is actually likely to vary across the different types of split ticketing, and is explored by looking at specific flavours of split ticketing later.

Muddling data insights

The sale of split tickets can muddle industry statistics, by giving the impression that fewer longer journeys are being made, and more short journeys. Whilst the data exists to stitch the short journeys back into long ones, the data isn't cleansed in real-time for all places that it is used. As a result, for example, revenue management systems may have a distorted view of the market demand, in-turn affecting their outputs of dynamic pricing/availability.

In addition to the impact on overall industry revenues, split ticketing can affect the apportionment of revenue between different operators, as regional operators attract a higher share of revenue on short distance fares than they would if an end-to-end fare was sold.

Can it be solved?

There are fundamentally two ways to solve split ticketing:

- Adjust fares and fare rules to attempt to eliminate scenarios where the sum of the parts is less than the whole.

- Institutionalise split ticketing, by routinely pricing journeys from the sum of the parts.

Neither is simple, nor fully effective, as explained further below.

Many different types of split ticketing

The concept of split ticketing arises from many different reasons.

The causes, impacts and potential solutions are different, so it makes sense to work through them individually.

Scenario 1: Journeys straddling peak/off-peak times:

This is hopefully one of the easier concepts to understand, illustrated by the following example.

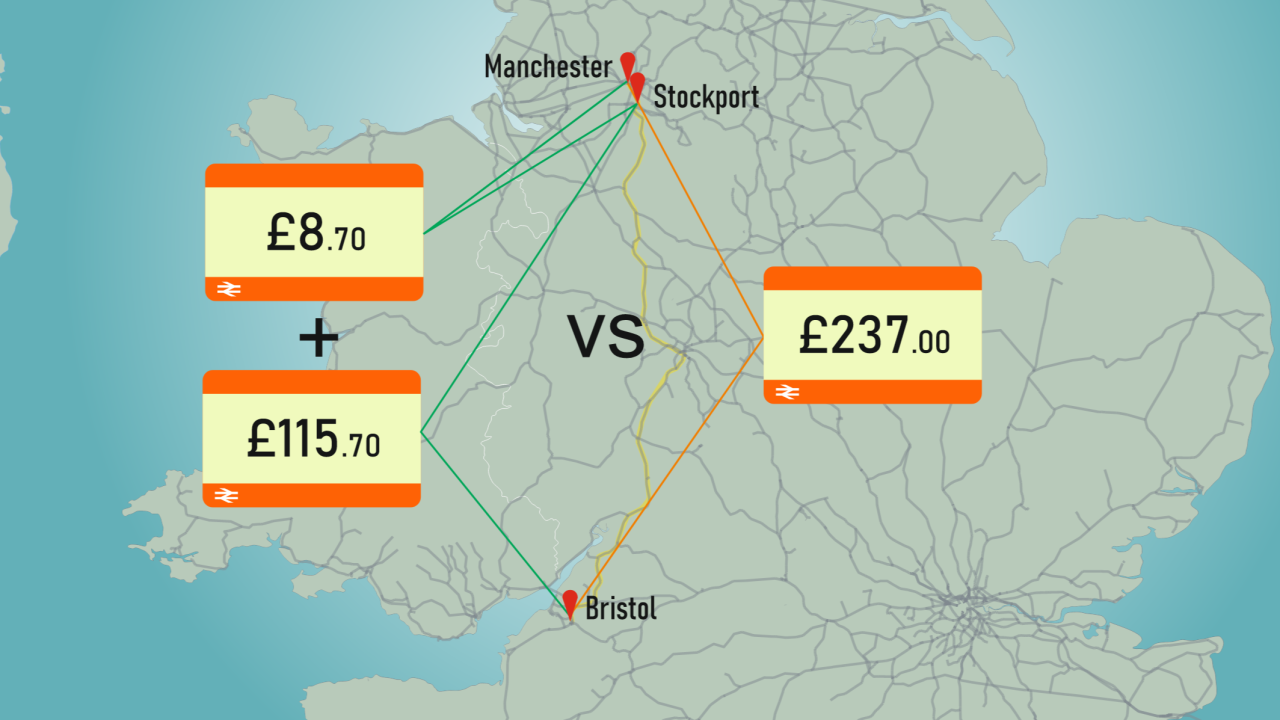

An Off-Peak ticket between Manchester and Bristol is not valid on trains departing before 09:30 on weekdays. The 09:25 departure from Manchester is, therefore, a peak time train.

Assuming I was making a return trip, outward at peak time but coming back at an off-peak time, the cheapest flexible tickets would be £237 (Anytime Single outbound for £122.60, and Off-Peak single for the journey back at £114.40).

However, as the train departs its next stop (Stockport) at 09:33, Off-Peak tickets are valid for journeys from Stockport. I could, therefore, buy local tickets between Manchester and Stockport (£8.70), and then an Off-Peak return ticket from Stockport to Bristol (£115.70) – a total of £124.40, saving £112.60.

Revenue impact:

Whether this grows or dilutes revenue probably depends on the nature of the route. If the peak time fares were rationally priced to optimise for the peak time market, a dilutionary impact would be logical – but in many cases it is questionable as to whether the peak time fare is in line with market. (Train companies have been incentivised to nudge customers away from flexible any operator fares, to single operator “Advance” fares)

This type of split ticketing also brings the benefit of softening the cliff edge between peak and off-peak pricing to better spread demand.

How to eliminate this type of split ticketing:

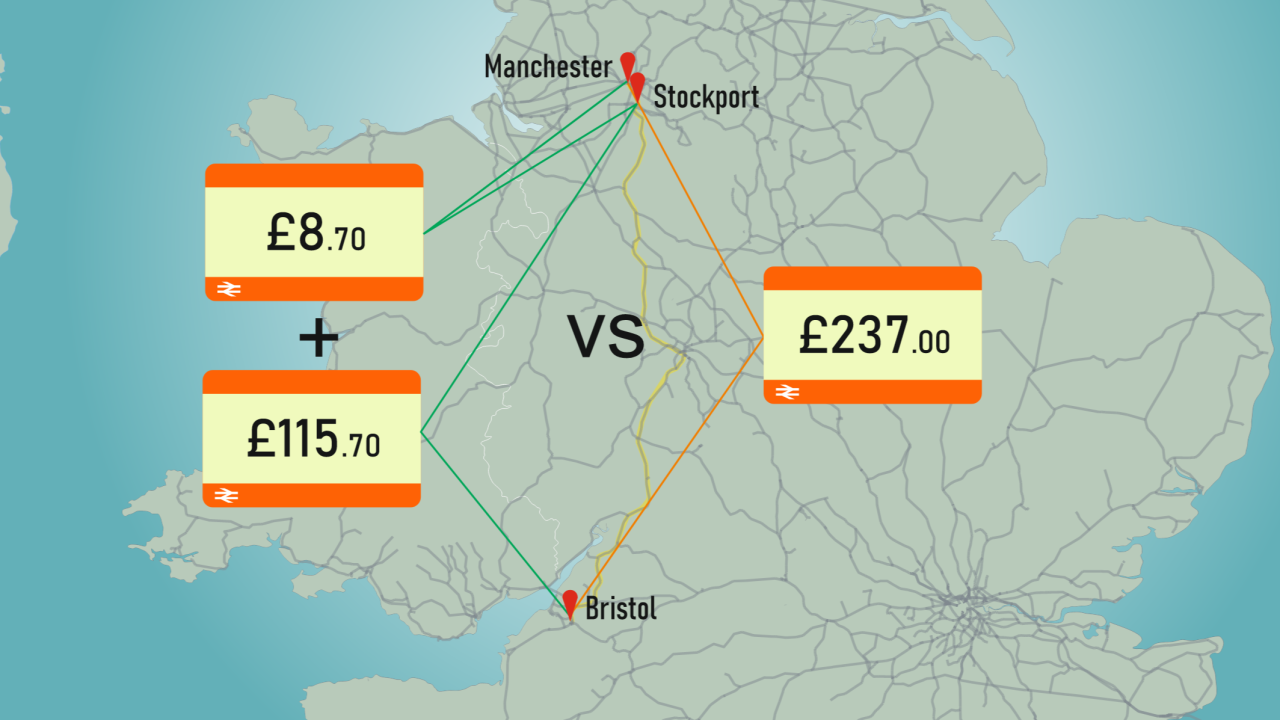

Some train companies try to avoid this issue, by varying the off-peak definition by boarding station. For example, on services between London and Cardiff there are a plethora of different peak times depending where you board the service (see below). This attracts a different criticism for making the definition of peak times more complicated to understand.

Scenario 2: Fares not defined for the end-to-end Journey

When train companies set fares, they must define what the fare is for each origin/destination combination.

As there are 2,500 rail stations, that’s potentially 6.2m combinations to price for every product, so in practice not all fares get defined for all combinations.

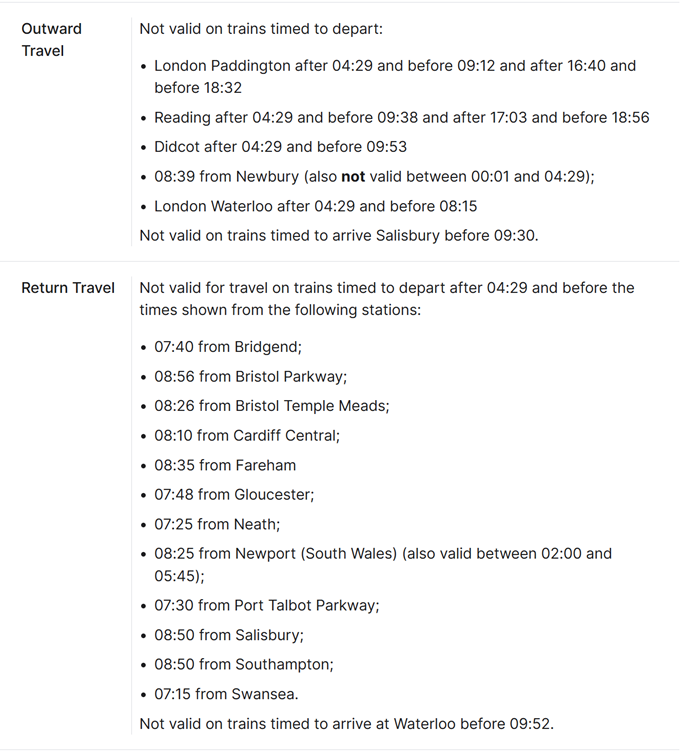

Let’s take a real example: For London to York, Grand Central has an Off-Peak Single fare, valid on its own services, priced at £70.70. Grand Central has priced this fare from London to York, but there is no such fare for Croydon to York. Instead, you have to buy the £179.10 Anytime single. Using split ticketing, however, you can buy the £70.70 option for London to York, plus £11.40 for Croydon to London, saving £97.

Revenue impact

In this scenario, it appears that split ticketing is mitigating limitations of the pricing system, and is likely to be revenue generative. Assuming Grand Central have rationally established that the optimal price for their service is £70.70, it cannot logically be optimal that this becomes £179.10 when combined with a short rail feeder leg.

How to eliminate this type of split ticketing

This type of split ticketing could be eliminated by systematically generating all relevant end-to-end fares, either as part of the pricing process, or as part of the fares engine in a journey planner. In effect, that would be doing this type of split ticketing by default.

Scenario 3: No availability for part of a journey.

The cheapest tier of tickets are “Advance” tickets. These tickets have mandatory reservations, and are sold subject to availability. There are generally multiple price tiers, and the cheaper tiers sell out first.

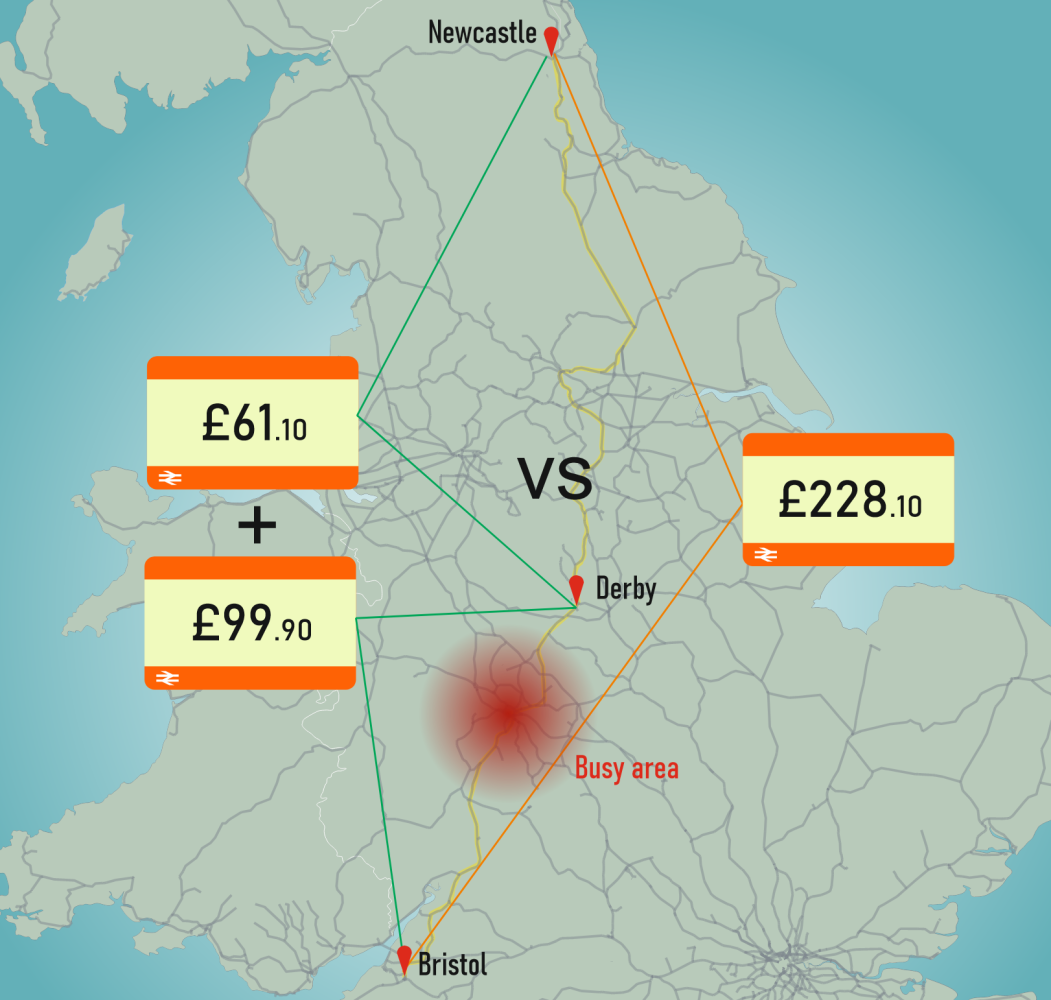

Availability can vary along a route. Let's take the example of a train from Newcastle to Bristol, that passes through Birmingham at a busy period. It is likely to have little, if any, availability of Advance fares through Birmingham, and therefore only the full price flexible tickets available.

However, I could buy an Advance ticket from Newcastle to somewhere like Derby, and then an Off-Peak ticket for the remainder of the journey (which can be sold regardless of seat availability).

Revenue impact

I suspect this scenario might also often be generative. In the absence of split ticketing some long journeys only offer full fare flexible tickets, despite these often being leisure routes with strong car and coach alternatives. The absence of availability on a short section of route results in an end-to-end price that’s out of kilter with the market.

How to eliminate

As with the previous example, one solution could be to systematically apply a split ticketing approach by design – treating the end-to-end journey as a series of sectors with different price points based on the demand per sector.

However, I’d also offer a more controversial solution: stop accepting local journeys on these services. Many other countries have a far clearer distinction between their long-distance services and their local services. In Britain we muddle the two, with long-distance services also acting as local services along parts of the route. In the franchised model, there was often an incentive to add more stops to a service to pick-up a share of the revenue. Perhaps GBR can take a more holistic approach, that better focuses long-distance services on the long-distance markets. By eliminating congestion caused by local journeys, the service can be more effectively priced to match the long-distance market it serves.

Scenario 4a: Pricing anomaly – caused by different markets

For the past 30 years, train companies have been incentivised to maximise their revenue within the constraints of fares regulation. Simplistically these means setting fares at a level that achieves the optimum balance between “conversion” (i.e. attracting people to use rail) and “yield” (i.e. how much they pay). Put the fares too high, and too few people travel. Too low, and there’s less revenue.

The problem is that the market conditions can vary a lot along a route. Historically long-distance early morning routes to London were able to command a premium, as a predominantly business market, with healthy demand. Short-medium distance routes into London were a commuter market with regulated fares, also with strong demand. There was, however, less demand for people travelling from far away to the intermediate stops. That meant that these routes were priced lower.

Individually each origin-destination pair was priced to optimise the revenue from that route.

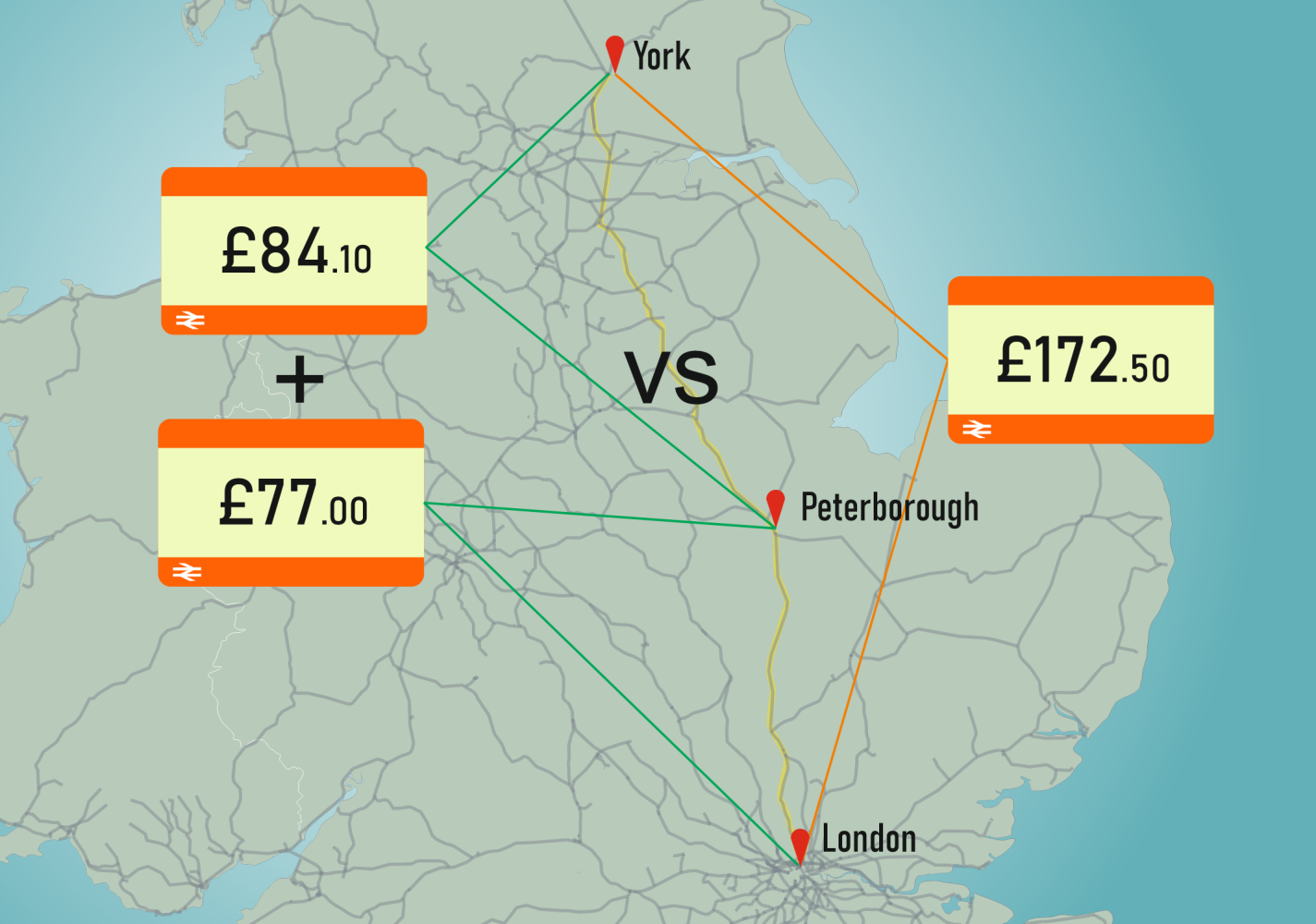

To illustrate this with an example: The Anytime Single fare for York to London is priced at £172.50 (the fare is not regulated so presumably this is optimal for the market); and the Peterborough to London Anytime Single fare is a regulated fare at £77.00 (i.e. government sets the maximum fare for this product). The York to Peterborough market, however, is much weaker, as car and coach are viable alternatives, and only commands an £84.10 peak fare. The result is that the sum of the parts (£77.00 + £84.10 = £161.10) is cheaper than the end-to-end fare.

Revenue impact

It is plausible that in this scenario split ticketing dilutes revenue, as it undermines the optimal price for the longer routes.

Logically if the generative effect of the cheaper fare offset the reduced revenue from the lower fare, then the operator would price at the lower fare anyway.

How to eliminate

This is one of the harder ones to solve. On a few routes that I’m familiar with, the approach to solving has been via increasing the fare on the “weak” sector. Protecting the price point on the higher volume routes, at the expense of making the weaker routes more expensive and even less attractive.

This is a helpful reminder that solving split-ticketing is not necessarily about passengers saving money, and in some cases some people will pay more, and parts of the network will be made less attractive.

Scenario 4b: Pricing anomaly – caused by regional boundaries

Over the years, local authorities and politicians have influenced local rail fares. This has been particularly prevalent around the major urban markets such as London, West Yorkshire and Greater Manchester. This has affected fare levels, fare design (e.g. zones) and policies such as peak/off-peak structure. It is a perfectly rational intervention, as rail fares need to fit in their local context alongside tube, light-rail and bus. However, this can result in a ‘cliff edge’ at the regional boundary (which is often in a geographically arbitrary place).

The impact can be positive or negative. Often the fares within “urban islands” are lower than the neighbouring area, but often have more restrictive peak time restrictions

For example, a common split location is East Croydon on the London – Brighton mainline. East Croydon is in London Zone 5, and hence the Croydon to London fare is effectively capped by the London Travelcard fare. The result is that for journeys from places like Gatwick and Three Bridges to London, it is cheaper to split tickets at East Croydon. (Gatwick to London Victoria £21.30 vs Gatwick to East Croydon £6.80 + East Croydon to London £8.50)

Revenue impact

As above, it is plausible that in this scenario split ticketing dilutes revenue, as it undermines the optimal price for the longer routes.

How to eliminate

As above, an approach to solving is to price up the outer sectors, but this results in these fares then being above what is optimal for that local market, making rail less attractive compared to alternatives.

Will it get worse before it gets better?

I’ve lost track of how many commitments have been made over the past two decades to simplify rail fares. And, despite some initiatives being successfully implemented, there is still a widespread view that fares are still too complicated. Split ticketing is a seen as part of the complexity, and messages about simplifying fares and solving split ticketing often get merged.

But will some of the initiatives to simplify fares actually make split ticketing more prevalent?

I think in places this might be the case, yes.

Single leg pricing

In the current fares structure, many single fares are only a few pence cheaper than the return fare, and in many places “Off-Peak Day” fares are only available as return tickets, not singles.

This limits the split ticketing opportunities, as split ticketing typically optimises on a single journey.

A proposed part of fares simplification is moving to “single leg pricing” where single tickets cost half the price of return tickets. This creates Off-Peak Single fares where they didn’t previously exist, and resolves the anomaly of single tickets costing just a few pence less than the return.

These new lower value single tickets also create a lot of new split ticketing opportunities.

Peak-time harmonisation

A common criticism of the existing fares structure is the plethora of different definitions of when an Off-Peak ticket can be used. There’s a strong push to harmonise on something standardised and simple – for example peak time is for departures before 09:30 and between 16:30 and 19:00.

Whilst something like this is far easier to understand, it will create new split ticketing opportunities of the type illustrated in scenario 1.

Could split ticketing be banned?

This is an issue that the industry has grappled with for years, and so far, has concluded that it is not feasible to ban customers for doing split ticketing. Ultimately the customer has a valid ticket for all parts of their journey.

There are procedural changes that could be made to hinder it, such as requiring customers to activate their tickets on the station before boarding a train (effectively meaning you’d have to leave and reboard a train to use split tickets). But these would be likely to get customer backlash, as well as creating operational issues as customers seek to frantically alight, activate a ticket, and jump back on a train.

Summary

In summary, split ticketing is an awkward concept. It’s virtually impossible to defend to a customer, and virtually impossible to systematically solve without negative impacts.

In places it resolves limitations of industry pricing systems, in other places it undermines pricing algorithms.

Radical changes to fares, such as a simple flat rate “pence per mile” pricing structure would conceptually resolve the issue, but would create far greater issues misaligning fares from the markets they cover.

Like it, or hate it, I suspect the gnarly issue of split ticketing will be around for quite some time.